At the start of the Final Major Project module (FMP), there are two options for viable research.

The first is alcoholism, the second is anorexia.

Both provide an opportunity to explore alternative relationships with food.

The initial idea was to produce a body of work based on research into alcoholism, this was the plan for quite some time.

The following are contemporaneous notes made as I externalise my decision to instead focus research on anorexia.

—

Arguably, anorexia, as a theme, is more relatable to food photography than alcoholism.

Food is a necessity, like water and air, we need it to survive.

But what happens when we start to regard food as a prison, trapping us in a body which we don’t want to be in, what happens when the balance of mind is affected?

What happens when our relationship with food turns sour, when food stops being a friend?

—

Jo is a recovered anorexic. She is a keen journalist and her diary keeping covers the period of her illness.

Diary entries record calorific intake and items of food consumed.

Freely admitting that her life has spiralled out of control, she lacks confidence and has low self-esteem.

What she eats is the one aspect of her life that she feels she can control and not eating provides her with a sense of achievement. It also helps her work towards her goal – being thin will lead to her being popular.

Pro-Ana websites have a significant influence upon her illness, and she finds that other users, mostly girls but not exclusively, refer to this as thinspiration and to themselves as ‘rexies’ and regard Ana, the vernacular term used by anorexics for the disease, as an (invisible) friend.

Consequently, the diaries also record phrases and images which were found by Jo to be inspirational.

Jo finds the culture associated with anorexia draws her deeper into a world in which she can be someone, a different person – the person she wants to be.

But this escapism has a price – denial of the reality which is the harm she is doing to her body as she starves herself.

—

Mental illness is heavily stigmatised and stereotyped – much work needs still to be done in educating people and reducing negative perceptions.

This holds true for eating disorders.

Anorexia is not a physical illness. It is a mental illness with visible physical symptoms.

Mental illness is not a taboo, it is not something to be hidden away – the most effective help we can all offer is to bring mental illness, irrespective of type, out into the open.

Such diseases are not something shameful, it is the way society regards mental illness that is shameful.

I believe that as photographers we have a duty to highlight social issues, to raise awareness.

‘Above all, life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference’ (Robert Frank)

I find food as a subject for photography enormously aesthetically appealing. The various ways in which we relate to our food fascinates me. Mental illness, how we regard those with mental illness and how we go about their treatment is a subject close to my heart. It is an area of considerable discrimination, ignorance and inadequate resourcing, all of which I have experienced first-hand as partner of, and carer for, someone with mental illness – including an eating disorder.

I want to know more about this mental illness and to understand more.

Jo-Ana is a way for me to extend my knowledge and understanding, and that of others, through photography.

Based on such close personal experience and a desire to further both my understanding and that of others, the project is being undertaken for both emotional and intellectual reasons (Scott, 2014).

I believe that this will be a cathartic process in addition to the outcome being a body of work which may help raise awareness.

—

What is the trigger? Are there multiple triggers?

Is there peer pressure before the influence of pro-Ana websites?

—

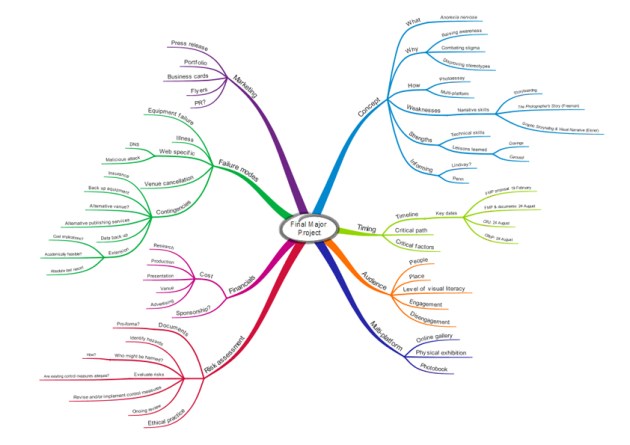

What – journal entries of a girl suffering from anorexia

How – still-life images

Why – raise awareness of the link between food and mental health, help remove the stigma associated with mental health issues

Reference

Scott, G. (2014), Professional Photography: The New Global Landscape Explained. Oxon: Focal Press