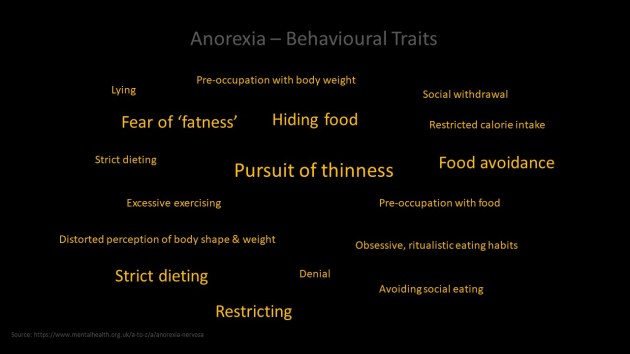

‘The Pro-ana community has turned anorexia (Ana) into its dogma. They venerate the illness giving meaning to their totalitarian “lifestyle”. It’s a virtual reality where they state commandments, share motivating tricks and exchange hundreds of images of thin models via their blogs. They have created Thinspiration, a visual new language – obsessively consumed to keep on wrestling with the scales day after day. Now, they evolved interacting with their cameras portraying their bony clavicles or flat bellies; or consuming extreme anorexic images, the Pro-ana have made Thinspiration evolve. I re-take their self-portraits, photographing and reinterpreting their images from the screen, resulting the visual response to the bond between obsession and self-destruction; the disappearance of one’s own identity. The project is a personal and introspective journey across the nature of obsessive desire and the limits of auto-destruction, denouncing disease’s new risk factors: social networks and photography.’

– Thinspiration, Laia Abril (2012)

–

Abril, 2012. Thinspiration – exhibition

Abril, 2012. Thinspiration – book detail

In her own words, Laia Abril’s photography examines the ‘most uncomfortable, hidden, stigmatized, and misunderstood stories’.

Interviewed by Anna Mola for Private Photo Review, Abril’s motivations for exploring eating disorders through the medium of photography are very clear.

The intention behind Thinspiration, Abril informs us, was to challenge the widely held misconception that all eating disorders are about a girl who won’t eat.

Abril favours working with subjects which are close to her personal experience. Subjects which, because of this closeness, she finds are easier to connect with and subsequently translate for an audience. Indeed, Abril has first-hand experience of one particular eating disorder, having suffered from bulimia for ten years before completing a year of treatment in 2010.

Seeing herself as an intermediary, Abril describes herself as visiting (mental) places nobody wants to go to, digesting issues and producing work which people can relate to and which evoke empathy.

Abril describes working in an intuitive way in the earlier stages of her career. She goes on to explain that whilst still developing in an organic way, her work is now more informed by her vision for the finished body of work and that experience in knowing what a finished body of work will look in relation to a given platform plays a major part in development.

Producing work which is consumed across a range of platforms simultaneously, Abril informs us that the initial platform for her work sets the mood for the work, and that this is fixed. However, she goes on to tell us that whilst work is produced with one particular platform in mind from inception, she does adapt work in later stages to suit alternative platforms with the essence, or the soul (mood) of the work remaining unchanged.

Generally, Abril’s work is produced initially as a photobook which she suggests offers the audience time to digest the difficult and complex issues which are the subject of her work.

With regard, however, to her multi-platform style of presentation, Abril identifies the complexity of the issues she examines, together with the need to work outside her comfort zone, as being the driving factors.

–

In terms of relevance to my photographic practice, it would appear that Abril and I share a common aim – that of educating to prevent.

‘Above all, life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference’ (Robert Frank).

I believe that as photographers we have a duty to highlight social issues, to raise awareness.

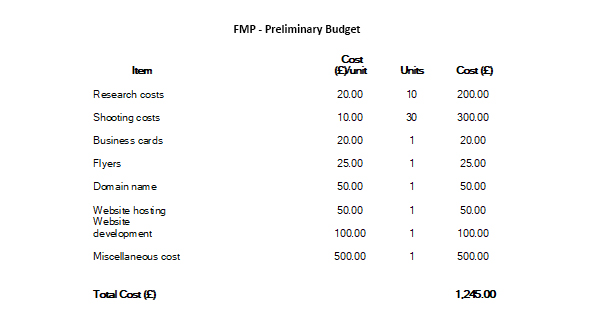

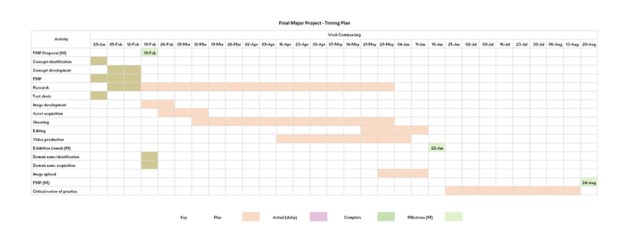

There were several different possible subjects for my Final Major Project and each one was explored for its advantages and disadvantages. Once I decided on exploring anorexia and the pro-Ana culture it seemed it seemed immediately natural to think in terms of publishing the body of work as an online gallery with accompanying audio-visual. It seemed equally natural to think about how the life of the project could be extended by producing a photobook, and further extended by exhibiting in schools and colleges.

It is, therefore, reassuring to receive confirmation that such a multi-platform, multimedia presentation strategy has been used so successfully by Abril.

I have a very clear vision for the way I want the online gallery to look, and this vision was established very early in the project. Other platforms will utilise the same images, adopted appropriately – again this intention was determined at the beginning and is a strategy also employed successfully by Abril.

Previously I have cited Goldin as one of the informers of my practice due to her preference for gritty, longform style documentary photography. It is, therefore, interesting to note that Abril also offers Nan Goldin as an influence upon her work.

Clearly, Abril is a skilled visual storyteller and an accomplished publicist. Working intuitively in the early stages of my career leads me to implement some of the strategies employed so skilfully by Abril.

This leads me, then, to ask the question what would I do differently?

References:

Abril, Laia (2018). ‘A Conversation with Laia Abril’. Conscientious Photography Magazine [online]. Available at: https://cphmag.com/conv-abril/ (accessed 07 March 2018)

Abril, Laia (2012). ‘Laia Abril – Thinspiration’. Private [online]. Available at: https://www.privatephotoreview.com/2012/10/laia-abril-thinspiration/ (accessed 06 March 2018)

Laia Abril (2018). ‘Thinspiration’. Laia Abril [online]. Available at: http://www.laiaabril.com/project/thinspiration/ (accessed 08 February 2018)

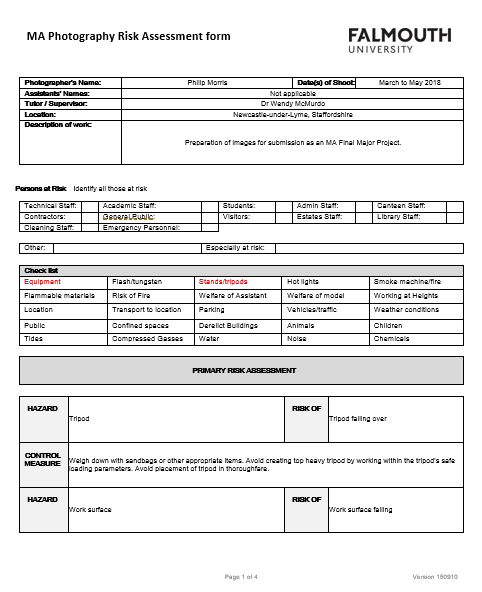

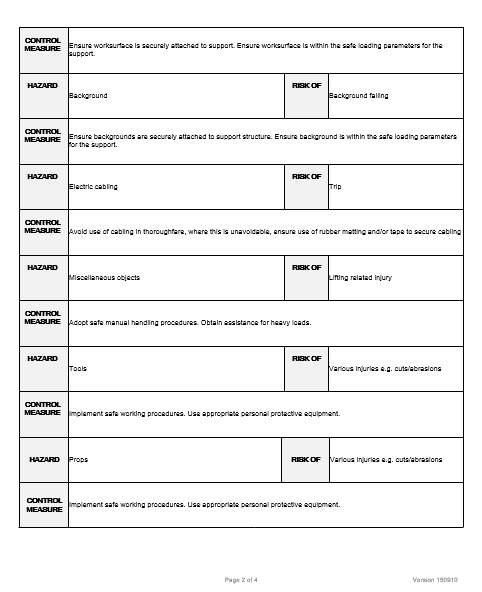

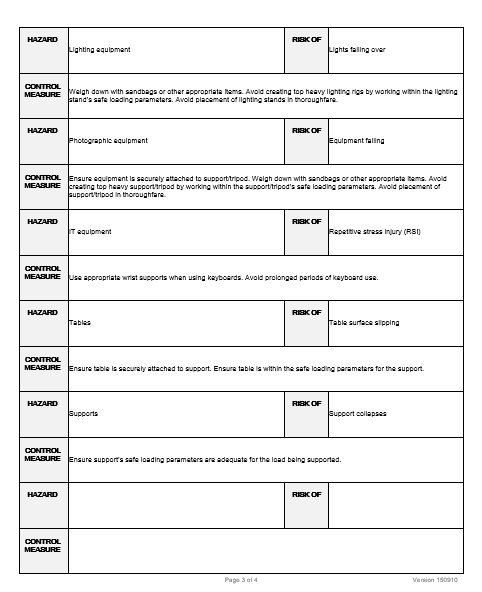

Risk Assessment – page 2

Risk Assessment – page 2

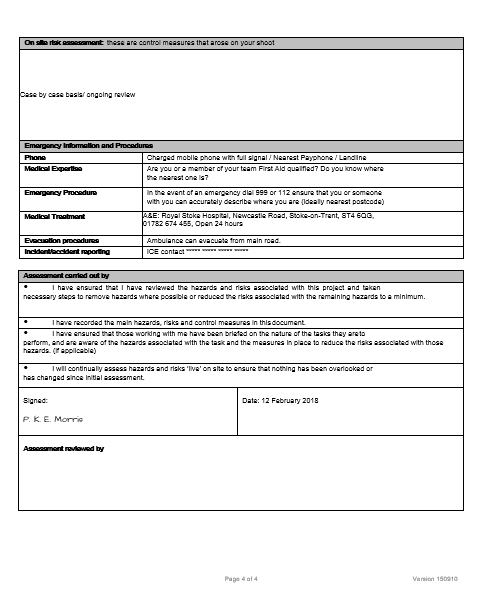

Risk Assessment – page 4

Risk Assessment – page 4